Emhoola peddled magic. He sold it by the cartload, and everywhere he went it was bought with self-deceiving gusto. He sold it in cheap brass compasses that no longer worked, in the shriveled corpses of pack donkeys whose heads lolled flea-bitten against the sales-rack strappings of his wagon, in straw dolls and dried frogs and mosquito paste and all variety of herbs and medicinal fungi.

Emhoola peddled magic. He sold it by the cartload, and everywhere he went it was bought with self-deceiving gusto. He sold it in cheap brass compasses that no longer worked, in the shriveled corpses of pack donkeys whose heads lolled flea-bitten against the sales-rack strappings of his wagon, in straw dolls and dried frogs and mosquito paste and all variety of herbs and medicinal fungi.

He was a collector of all things collectible, and he purveyed these wares with a rag and bone man’s pitch few could resist.

?Freedom,” he’d call out, as he strode the dusty main streets of America’s new and little known frontier colonies. ?Freedom for one and all,” waving dehydrated chicken gizzards before him, urging on his old yak Bray with musty carrots on a fishing line.

People flocked to him everywhere he went, and bought his magic charms in droves. He told them he was a wizard, and so he was, though few knew more than the obvious. He marveled them with sleight of hand and he changed their lives with his premonitions and predictions. Those that bought the dead horses found flies no longer alighted upon their heads. Those that bought his watches found they were never late. Those that bought his onionskin sheaths kept knives which never dulled. Those that paid for his advice found their lives running clear and smooth as the Mississippi.

He was happy, as far as he had any emotion. But the happiest he ever was, was probably the time the citizens of Summitville tried to kill him.

*

It was a sultry southern day, Bray’s ears hanging wilted by her fleshy jowls, when the three town officials in their spruced top hats and waistcoats in the sweltering noon sun accosted his wagon. They held papers and brown leather briefcases, and one of them sported a monocle. They accused him of witchery under statute of the witch-finder general. They ordered him clapped in irons and delivered to the courthouse for verdict. Five men packing six irons and marshal stars followed. Emhoola let them do as they would.

They took his cart, ‘ appropriation’ they called it. He didn’mind. He threw up his hands and let his hands be fixed with the metal bracelets. One of the marshals, Byron Hereford, spat in his face and called him a ?son of a whore gypsy queer.”

He allowed them to lead him roughly to the jailhouse, a squat block of stacked granite and the only stone structure in town. By the Sheriff’s desk they stripped him and took to spanking his raw backside with a 10 length of leather reserved for horses.

?Gettin’ a confession,” is what the man Byron called it. ?I’m jes’ gettin me a confession.”

His men laughed. When he tired they took it in turns to wield the whip.

?We don’take to your gypsy witch type here,” said another, name of Eboni Workman, lifting the lash and dropping it. ?We gon’ make an example of you, boy. See here, Sprightly Jim?”

He pointed out a pudgy bald man with sweat rimed in sooty escarpments up his forehead. ?Sprightly Jim here,” he said, ?he’s making us a gibbet. You know what a gibbet is, magic man?”

Emhoola said nothing.

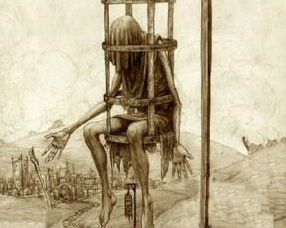

Eboni laughed. ?We’s all nice people roun here, but you’ve drove us to it. Gibbet is a cage in the shape of a man, jes’ about the size of your body, friend. We try you tomorrow, they stick you in the gibbet, and we wait. Byron reckons it’ll be a coupla days fore you’re all gone. Hang you up like that out front of Summitville, so’s all your friends are gettin’ the idea what kind of place this is. You like how that sounds?”

Emhoola said nothing.

?Nothing to say?” said Byron. ?Perhaps you like this, eh?” and he whipped Emhoola’s face. Blood flowed down his chest. The men roared with laughter, but Emhoola remained silent ?I’ll go until you scream,” said Byron, ?you understand?” He turned Emhoola’s chin and punched him square on the nose. ?You understand, gypsy queer?”

*

By dark Emhoola’s skin was flayed and ribbon raw, but he still hadn’screamed. Byron was exhausted, and Sprightly Jim had gone to work on the gibbet, Eboni to the courthouse to ready the jurors. He could scarcely curse the peddler any further, let alone send out another lash, so he gave the job to somebody else. He sent word out for Gardener Roy to come in.

?Types like you,” panted Byron, ?you’re no good for a nice place like Summitville.” Then he shoved Emhoola into his steel cage for the night and locked the door. Emhoola didn’sit, he only stood there, staring out of the gloom. Byron ordered him to sit down. He shouted and threatened the lash, but Emhoola only waited, and stared.

Eventually Byron returned to his desk, and snoozed until his replacement came in gone midnight. He looked back at Emhoola once as he left. ?You’re in trouble now, boy,” he said. Then he was gone, and Emhoola was alone with Gardener Roy.

Gardener Roy had earlier that day drowned a bag of kittens in the local river because he was bored. He dipped them, drew them out, dipped them and drew them out again. Occasionally he opened up the bag, let those still alive wander out in a watery daze, mewing pathetically, then he shoved them back inside with their dead kin and dunked them until they mewed no more.

He grew up with a moonshine father and wisp of a mother. His father beat them both half to death almost daily, then afterwards when he was sotted he cried and told them he loved them. The next day he would beat them again with a plank of firewood, or a pick handle, or a length of tarred rope. Sometimes he would hold them down and stare into their eyes while pinching their flesh raw with his bare hands.

At the cage Gardener grinned his father’s grin, unlocked the iron door, closed it behind him, and stepped up to the still standing Emhoola with a fire poker in his hand. ?You and me,” he said, low tones and light in his eyes. ?You and me gonna dance, boy,” he said.

And so they danced. Emhoola didn’cry out once.

*

The next day they dragged him pale of face and bloodied to the courthouse. On the way he saw his cart vandalized and smashed, his yak Bray beaten to death and bloody on the dusty Summitville main street. People who once bought his charms and welcomed his advice hurled rotten fruit and stones at his face. They cursed him and spat in his hair. One woman rubbed onions in his eyes.

In the trial the prosecution branded him a cheat, a thief, a gypsy, a queer, a witch and a warlock thrice over. They charged him responsible for the summer’s humid drout, for the plague of locusts which had swarmed the scattered seed in early spring, and for the inclement Arkansas soil. They charged him with the miscarriage of Sheriff Byron’s first child, with Derrick the baker’s bread no longer rising properly, and with the fact that Jim Sprightly’s wife had contracted scarlet fever. They charged him responsible for the collapse of the old schoolhouse and the burial alive of the children, one of them Eboni Workman’s son.

His witnesses proceeded as follows: Byron Hereford, Jim Sprightly, Eboni Workman, Gardener Roy, and the town mayor, Silvio Glesas. They all condemned him as the man that sold them hexed trinkets, the man that sold them out to the devil, and they promised to sell him right back.

They had the completed gibbet hanging in the courthouse with them. Every time one of the witnesses in their testimonials pointed to it, the audience cheered. Gardener Roy pointed a lot. His sotted father in the audience wept and told all that would listen: ?that’s my boy!”

His own lawyer, the defence, stood once and objected mildly, asking for lenience in the face of so many crimes, such that his client be slain quickly, before he was placed in the gibbet.

The appeal was denied. Emhoola was asked if there was anything he wanted to say. He rose. They made him swear on the Bible. The courthouse held its breath.

Emhoola looked around, into the eyes of his murderers. Then he farted. Long and low and loud.

They lynched him there and then, audience members vaulting their stands to lay a hand on him, pummel him, tear out his hair, gouge his eyes. By the time he reached the gibbet and was laid inside, he was missing half his hair, several tooth, an ear, and one of his eyes was swollen shut and oozing clear liquid. His nose was broken and bleeding. His thighs had been stabbed at and were red with blood.

?Filthy bastard!” the people cursed, and dusted down their hands of the whole filthy business. They let Gardener and Byron and Eboni drag him in his gibbet to the edge of town, and there they strung him up from an oak tree. Gardener Roy took out a pair of gardening shears and held them up for Emoola to see.

?Gonna get me a souvenir,” he said. ?Of the best dance-partner I ever had. You want one, Byron?”

Byron nodded that he did.

Gardener delicately cut off Emhoola’s shoes, peeling them away from feet stained with run down blood. Then he started cutting off his toes. Emhoola made not a sound. Gardener piled the toes up on the ground, gestured for the lynch men to take one each. They did. Then he moved onto the fingers, and took them all. Emhoola didn’struggle once. These Gardener took back into town with him, and gave them out to his friends and neighbors. His own he skinned and dipped in gunmetal-acid until there was nothing but bone, then he bored a hole in the knuckle and wore it on a thong round his neck. His own magic charm, he called it, from an honest to goodness magic man.

Emhoola was boiling with happiness. Bleeding and dying and pained, he watched the sun set that night, and knew he would not last ’til the morning.

*

The next day the children came. They threw dirt and rocks at his corpse, though he was dead by then, and long past caring.

*

The day after that his body was gone from the gibbet. Nobody knew where it had gone. Some presumed he was just eaten. Others said he’d magicked his way out of there, and were afeared. None had ever dealt with a warlock in such a way before. But those that feared were reassured by those that spoke plain truths, that there was nothing left of Emhoola the peddler at all.

*

That night he came back. He raised his yak Bray from her hastily dug grave in the town’s slag pit, and he reassembled his cart with moonlight as his tool. He visited every house where his body parts lay, and he knocked on the doors soundlessly, glided through the walls, entered the bedrooms of all who had wronged him, and dipped his icy blue ghost fingers into their hearts, tore out the spark from within, and swallowed it down.

At Byron’s place, run down and surrounded by scrub grass jutting through the gaps in his white picket fence, Emhoola paused. He hefted a length of moonlight in his hand, entered Byron’s bedroom, and woke him. His screams were instantly muffled. His wife died of a heart attack in their bed. Emhoola whipped the man to death. The sliver cut right through Byron’s flesh, drew no blood, but lighted upon his soul. The moment before death, Emhoola seized up the spark and gobbled it down.

At the homes of Jim Sprightly, Eboni Workman, and all those who spat, all those who cheered, all those who took a piece of his earthly body away as a souvenir, he did the same thing. He sealed their lips so they couldn’scream, then ran them aground in their beds, pressing his fingers into their eyes, ears, puncturing their bodies, seeking out the renegade spark and sucking it back. They tried to fight him, but there was nothing there to fight.

At Roy Gardener’s house he slowed his pace. He took his time. He sidled up the beaten old porch, swing creaking in the hot stale air. He could smell ripe moonshine and vomit in the sawdust lining the worn wooden panels. He stepped through the porch screen and entered Gardener’s room, where he lay with a young trollop from the village, some 13 years old. Emhoola stroked her heart and she screamed and tore from the house. He woke Gardener slowly, but when he saw the spike of moonlight in Emhoola’s hand, he screamed.

?I didn’mean it, I didn’mean to,” he cried, as he saw the low light in Emhoola’s ghost eyes. His pa came in to beat him silent, but Emhoola stole the spark from his heart without even turning. Roy watched his father sink to the ground without a sound and fell to mimsied whimpering.

?Now,” said Emhoola, holding the shaft of moonlight before him so it glinted in Gardener’s eyes, ?we dance.”

*

By morning Roy Gardener was a shivering wreck. He wept constantly. His nose ran and he had fouled himself numerous times throughout the night. When he was done, Emhoola tossed away the moonlight shaft and stood over Roy, who shivered and held his hands before him, begging.

Emhoola leant down, touched his icy ghost lips to Gardener’s trembling ear, and spoke.

?I’ll be your gibbet,” he said, then reached into Gardener’s chest, scooped out his spark, and wolfed it down.

He left the house and saddled Bray, hooked her onto the cart, and gathered his scattered wares back into their proper places. He left Summitville that night with 47 dead in his wake and a bellyful of sparks, headed for the skies. In as much as he was ever happy, Emhoola was at his happiest then.

Behind him, as morning dawned over Summitville, the first screams of the day rang out.

END

DARK FICTION

You can see all MJG’s stories here:

[album template=compact]

Comments 4

I hardly comment, but I really enjoy your stories. Thanks for sharing them with us!

Nice story Mike, a bit gruesome, but enjoyable nonetheless!

Haha! That showed ’em!

Really enjoyed reading this I liked it!